Howard Stern have a dangerous disease revealed

After a health crisis that had him “scared? s***less,” the $90 million radio personality opens up about retirement, Trump and his personal and professional metamorphosis: “I’d feel really f***ing s***ty if I hadn’t evolved.”

On Wednesday, May 10, 2017, for the first time in memory, Howard Stern abruptly canceled that day’s show. His listeners, a famously loyal subset of SiriusXM’s 36 million subscribers who’ve made the boundary-pushing “shock jock” a part of their lives since he rose to prominence in the ’80s, were understandably alarmed. Reddit lit up with crackpot theories, and a handful of dogged reporters tracked down the host’s elderly parents to check up on him.

By Monday, the self-described king of all media was back on the radio, poking fun at the hullaballoo, as many hoped he would. It was just the flu, he told his audience: “Why is it such a big deal that I took a fucking day off?”

Turns out, he was lying through his teeth.

On the morning in question, Stern wasn’t home with a fever or runny nose; he was being carted into surgery. For the better part of the previous year, he’d been shuttling between appointments as doctors monitored a low white blood cell count revealed during a routine checkup and, later, discovered a growth on his kidney. The chance that it was cancerous: 90 percent.

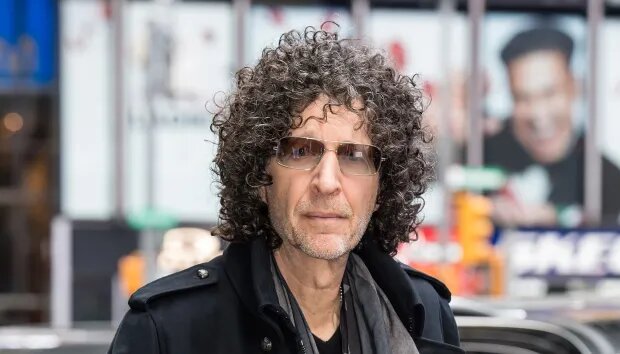

For a man who lives his life on-air, divulging such personal details as his first wife’s miscarriage and his reputedly undersized penis, he’d been uncharacteristically discreet about his latest struggle. In fact, he told only his very inner circle, a group that included his second wife, Beth, his three daughters, his therapist and his on-air foil of nearly four decades, Robin Quivers, herself a cancer survivor. Until all this, Stern had considered himself invincible — at 65, his 6-foot-5 frame was still enviably trim, his head endowed with a thick mop of curls. He ate well and exercised often. Cancer was a ridiculous notion.

“And now all I’m thinking is, ‘I’m going to die,’ ” he recalls in an interview, his first time discussing the health issue publicly. “And I’m scared shitless.”

A couple of hours and seven incisions to his abdomen later, he came out of surgery to learn it had all been a scare. A tiny, harmless cyst. The news should have been comforting. But for the first time in Stern’s adult life, he’d come face-to-face with his own mortality, and now there was no turning back.

In the 24 months since, he’s found himself wondering often if he’s done it all wrong. Despite amassing fame and fortune unrivaled in his medium, Stern says he’s a mountain of regret. He beats himself up over the father he couldn’t be to those three girls, now grown and living elsewhere; and the husband he never was to their mother, Alison, who finally left him in 1999. He can’t read his first two best-selling books, Private Parts (1993) and Miss America (’95), without cringing at his own narcissism, and he insists nearly every one of the interviews he conducted during his pre-satellite radio days makes him sick.

“I was so completely fucked up back then,” he says, his head shaking with disgust on this morning in early April. “I didn’t know what was up and what was down, and there was no room for anybody else on the planet.” His more recent metamorphosis, the result of age, a healthy marriage and intensive therapy, has revealed sensitivities he didn’t know he had. It’s also sharpened his skills as an interviewer.

Dressed now like an aging rocker with a pair of dark jeans, boots and his signature shades perched just above his brows, Stern is sprawled out on the charcoal-gray couch usually reserved for guests in his midtown Manhattan studio. He’s explaining how his brush with cancer is a key reason he agreed to write his first book in two decades, Howard Stern Comes Again, a curated collection of edited transcripts from his favorite interviews — with everyone from Billy Joel to Donald Trump (more on him later) — wrapped in his own memories and candid self-reflection. There’s considerably more in the book on his health scare, too, along with his musings on fame, sex and spirituality. “It’s as much his autobiography in conversation as it is a tour through American pop culture over the last 20 years,” says Jonathan Karp, publisher of Simon & Schuster, which will release the book May 14. That brush is also the reason Stern’s been having real discussions about what’s next once his contract with SiriusXM, which reportedly pays him $90 million a year, expires at the end of 2020.

“I’m at a place now where I am trying to figure out how to spend the rest of my life, however long that might be,” he says. He’s been flirting with the idea of retirement in conversation with close friends and, occasionally, on the air. “It seems weird to me not to have this,” he nods at the desk where he spends four to five hours three mornings a week — but maybe it would be great. Maybe his painting could improve. Maybe he could take that sketch class he’s been thinking about. Maybe he and Beth, 46, and their coterie of rescue cats, could travel more, visiting those kids he doesn’t get to see enough of.

He wouldn’t be bored, he’s sure of that; but is Howard Stern really ready to shut up?

America’s most recognizable radio personality has been screaming for attention his entire life. Early on, it was through performance: dirty puppet shows for his pals, impressions for his parents. His radio engineer father would offer feedback, if not exactly encouragement — and a valuable lesson in how to keep an audience engaged. “Stop!” his dad would bark. “You’re going on too long! Make it interesting!”

By the time he hit puberty, Howard’s Long Island community had transformed from predominantly white to predominantly black. As he recalls, the arrival of black families prompted his so-called liberal neighbors to flee in the middle of the night. It was an early education in hypocrisy, and it left him outraged: “All these preachy phonies who would go to services and say, ‘All people are the same in God’s eyes’ were full of shit,” he seethes. His parents, along with Stern and his older sister, Ellen, would stay put. By his freshman year of high school, he was one of only a handful of white kids left in class, a de facto outsider who’d frequently find himself on the receiving end of somebody’s fist.

The Sterns eventually relocated to a nearby white neighborhood, but by then Howard was woefully behind academically and a complete disaster socially. “I was traumatized,” he says. Still, he got admitted to Boston University, where he found an outlet on the campus radio station and later a series of gigs that took him from Hartford to Detroit. In the early days, he’d shake every time he got on-air; but with time, he began to relax and find his voice, a mix of hijinks and puerile humor.

By the early ’80s, Stern landed in D.C., where he was first paired with Quivers and, through a series of outrageous antics, sealed his shock jock reputation. No prank seemed to get quite as much attention as the one he pulled the morning after an Air Florida flight crashed in the Potomac River, killing 78 people. The host famously pretended to ring the airline, inquiring about the price of a one-way ticket to the 14th Street Bridge. Those who weren’t horrified were highly amused. From there, Stern moved to New York, the most coveted of markets, where he shared with format predecessor Don Imus a station and a slogan: “If we weren’t so bad, we wouldn’t be so good.” By 1986, his eponymous show was nationally syndicated.

With each stunt, Stern’s audience seemed to grow larger and more passionate. At its peak, The Howard Stern Show reached an estimated 20 million weekly listeners. Money followed, though the number of zeroes seemed important to him largely as a measure of success. Save a few pricey homes — in Manhattan, the Hamptons and Florida — the borderline recluse has never been known as a big spender or a man of lavish taste. (Money is the rare subject that Stern has long been unwilling to touch, unless of course he’s the one asking the questions.) Winning, on the other hand, “became an almost debilitating obsession,” he says. He was committed to doing and saying pretty much anything to stay on top: be it dialing for dates with lesbians or banging bare bottoms like bongos. At one point, one in every four cars on Long Island was listening to The Howard Stern Show during the morning commute; he was fixated on the other three: What the hell were they listening to if not him?

For years, guests served merely as props, there to service Stern’s audience. “My interviewing technique was like bashing someone in the face with a sledgehammer,” he writes in the new book. “I was like the Joker, and all I wanted to do was cause chaos.” He asked Gilda Radner if Gene Wilder was well endowed, driving her right out of the studio. He spent the bulk of his time with Carly Simon telling the singer how hot she was; and, despite multiple warnings not to ask George Michael about his sexuality, he did so immediately. There were plenty more, from Eminem to Will Ferrell, who appeared once then never again.

Leave a Reply